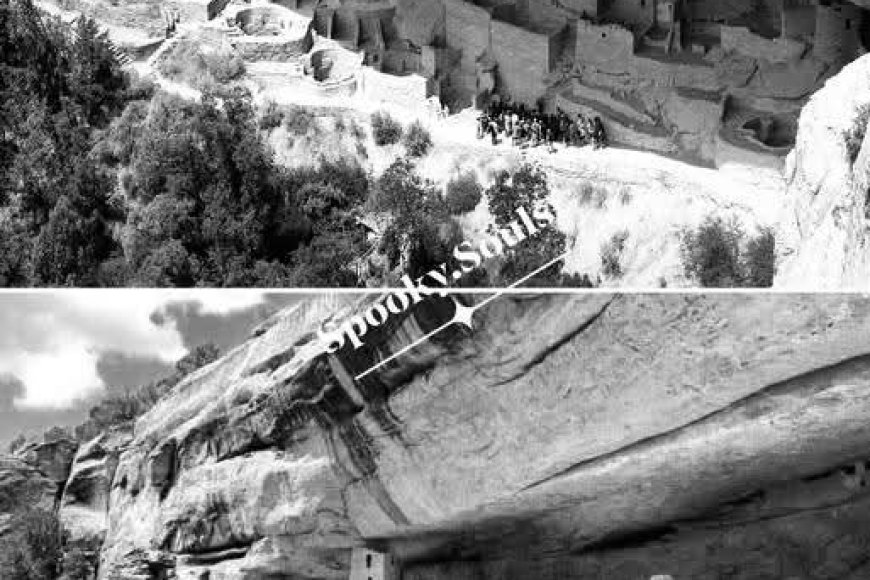

Between the towering sandstone walls of southwestern Colorado lie the silent ruins of a people whose ingenuity turned rock into refuge. From ca. 1190 to 1300 CE, the Ancestral Puebloans sculpted entire villages into the alcoves of Mesa Verde’s cliffs, fashioning a landscape both protective and sacred. Today, these cliff dwellings stand as North America’s most extensive and best–preserved testimony to a lost way of life.

Carving Home from Cliff

Perched dozens of meters above canyon floors, the multi–story complexes at Spruce Tree House, Balcony House, and Cliff Palace harness the natural alcoves for year-round comfort. Thick adobe mortar binds sandstone blocks into walls; timber beams—harvested from nearby piñon–juniper forests—support second floors; and plastered interiors once glowed with painted murals and woven mats.

-

Temperature Control: Deep overhangs block summer sun while trapping heat in cooler months.

-

Water Management: Rock–cut reservoirs and carefully graded channels channeled seasonal runoff into cisterns below.

Centers of Community and Ceremony

At the heart of each settlement lies the kiva—a circular subterranean chamber used for religious rites, social gatherings, and governance. Vaulted ceilings once held wooden roof ladders; central fire pits warmed assemblies beneath symbolic murals and sipapu (ceremonial “portal” stones) that evoked emergence from the underworld. Surrounding plazas served as marketplaces and playfields, while storage rooms hewn into recesses preserved maize, beans, and squash against the arid climate.

Daily Life on the Ledge

Archaeological finds paint a portrait of resilience:

-

Agriculture: Narrow mesa tops yielded terraced fields. Dry–farmed corn, beans, and gourds grew in rocky soils, enhanced by carefully applied compost.

-

Craftsmanship: Pottery vessels display intricate black-on-white designs; woven sandals and baskets attest to sophisticated plant-fiber techniques.

-

Trade Networks: Turquoise, shell beads, and exotic copper bells hint at long-distance exchange reaching as far as the Gulf Coast and the northern Rockies.

Mystery of Abandonment

By ca. 1300 CE, after a century of thriving occupation, cliff-side life came to an abrupt end. Scholars debate causes—prolonged drought, resource depletion, social strain, or spiritual renewal—but the outcome was unanimous: Mesa Verde’s people migrated south and east, their stone homes left to time and wind.

Preservation and Legacy

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978, Mesa Verde National Park now protects over 4,000 archaeological sites. Rigid conservation efforts guard the fragile sandstone façades, while controlled visits allow modern explorers to climb ladders and peer into chambers once echoing with song and prayer.

-

Erosion Control: Noninvasive scaffolding and water-shedding caps slow decay of exposed masonry.

-

Community Collaboration: Descendants in the Hopi, Zuni, and other Pueblo nations guide interpretation, ensuring cultural traditions endure alongside scientific study.

Stones That Speak

Today, in the hush of canyon breezes, the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde whisper of human adaptability and spiritual depth. Their circular kivas still frame shafts of sunlight at solstices; their walls retain faint carbon-black murals. As visitors tread ancient pathways, the canyon seems to remember every footstep, every prayer, and every hammer that shaped these silent homes. In their shadows, we glimpse a past that lives on—not as mere ruin, but as architecture woven into the very soul of the rock.